CREATING THEATRE IN A PANDEMIC: REVIEW for WESTON'S "ONE ROOM"

- Laura Stanczyk

- Aug 26, 2021

- 4 min read

Review: Packing 14 Up-to-the-Minute Monologues in ʻOne Roomʼ A collection of short solo works from the Weston Playhouse furthers the redefinition of theater online — and of life in isolation. By Jesse Green Aug. 10, 2020 Five months into internet exile, playgoers have a lot of questions. Two of the biggest for me are: Is what we’re seeing online really theater? And why so many monologues? The second, at least, is easy to answer. One-person plays are cheaper, easier, quicker and safer to produce. No one breathes on anyone. The costumes can be scrounged. Monologues also avoid the “why is she staring past his elbow?” problem that’s endemic to productions in which actors have to pretend to maintain eye contact when they’re really miles or continents apart. But the monologue question and the existential one are actually bound together, as a new slew of one-person mini- dramas from the Weston Playhouse in Vermont demonstrates. Presented on YouTube under the omnibus heading “One Room,” this collection of 14 original works, most of them five to eight minutes long, makes a case for the solo direct- address form as the irreducible essence of theater, an essence that even a pandemic (or iPhone) can’t denature. The pandemic is thematically central to the 14 offerings, which you can view singly or in a 95-minute compilation that debuted on Friday evening. The theater’s prompt to the playwrights — “What makes a home? What stories might be hiding in its ordinary rooms?” — naturally suggests content in which characters are stuck considering their lives while socially distanced. Death, illness and ghosts are common denominators here, as is longing for the lost world and its pleasures.

At their best, the monologues use our singular moment to intensify feelings about eternal matters. In the evening’s standout, a play by Noelle Viñas called “Zoom Intervention,” a mother undergoing chemotherapy talks online to her son, a drug addict she can no longer allow into her home. (The emotional danger he has always brought with him is also now a literal one.) Simple as the setup is, the Off Broadway treasure Liza Colón-Zayas gives it the full complexity of drama: Her wrenching, radiant performance imbues the mother with so much love that it nearly (but not quite) swamps her anger. Great performances are crucial in monologues, especially short ones, because there’s no compensation to be sought in the rest of the cast and because the material is always more or less a sketch. (That said, Viñas’s play, directed by Estefanía Fadul, is beautifully structured and as long as it needs to be.) Like Alan Bennett’s “Talking Heads” and the pandemic series “Viral Monologues,” the “One Room” pieces are especially welcome as opportunities to experience terrific actors, whether newcomers or veterans, displaying new sides of themselves. Among those unfamiliar to me, I especially enjoyed Jakeem Dante Powell, whose emotions shift like the colors of a mood ring in “Rita,” by Josh Wilder. The story of a young Black man sequestering in his apartment, it is, in part, a portrait of boredom, in which “I tried something new today” is a refrain that changes its meaning with each repetition. (Reginald L. Douglas is the deft director.) But it is also, by suggestion, about political engagement, and brings to that subject an allusive grace lacking in some other treatments of the theme.

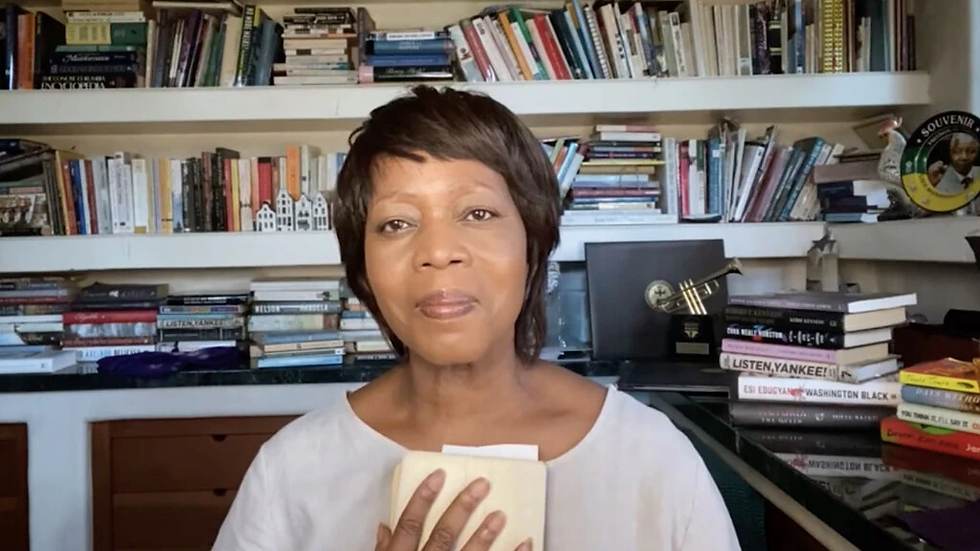

The better known actors include Daphne Rubin-Vega, delivering a knockout performance in Dael Orlandersmith’s “before the witching hour / pandemic blues.” A series of memories of city life recalled as the clock lumbers from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m. before a night of curfew, the play has a hermetic, poetic quality that could have been difficult to vivify. But under the direction of Jade King Carroll, Rubin-Vega brings an intense specificity to each memory — the names of streets, the expressions on faces — so that even when you don’t have a matching experience, you know exactly what she’s feeling. What she’s feeling is loss; so is Josh Hamilton’s character in Andy Bragen’s “Memories of New York,” which bears the subtitle “and other things that are gone.” Beautifully directed by Knud Adams, with Hamilton in a rowboat in a gray shirt against a gray sky, it’s really just an expertly delivered list of pandemic deprivations that eventually become indistinguishable from life’s: street fairs, Times Square, youth. What Alfre Woodard’s character, a former kindergarten teacher, has lost in “A Room of Nobody Else’s” is not so evident, but this being a play by Will Eno, the enigma is key to the dramatic construction. Along with David Cale’s “The Actor,” this is one of the “One Room” plays that seems to offer a trick answer to the theater’s prompting questions. In “The Actor,” featuring Marin Ireland and directed by Lee Sunday Evans, the happy ending that isolation allows for a couple stuck in a bubble together feels skillfully wrought but shallow.

Isolation provides a more literal happy ending for Dana Delany’s is-she-demented-or-is-she-just-lonely character in “The Visitations” by Jen Silverman: a suavely comic ghost story in which the socko punchline (perfectly pulled off by the director Mike Donahue) doesn’t seem like an evasion but a payoff. That’s not so easy to do; several other monologues in “One Room” fizzle on their way toward attempts at catharsis, perhaps the result of working too hard in too little space. Monologues shouldn’t be agendas. And yet in its own way, Eno’s play, directed by Kenny Leon, delivers one. Marvelously austere in its epigrammatic ambivalence, it kicks off the compilation and lingers over the 13 plays that follow. As if addressing this new kind of theater we’re seeing as well as this new kind of life we’re living, Woodard, sublime, looks right at the camera and says prayerfully: “We need people to help us do the things we need to do alone.”

Comments